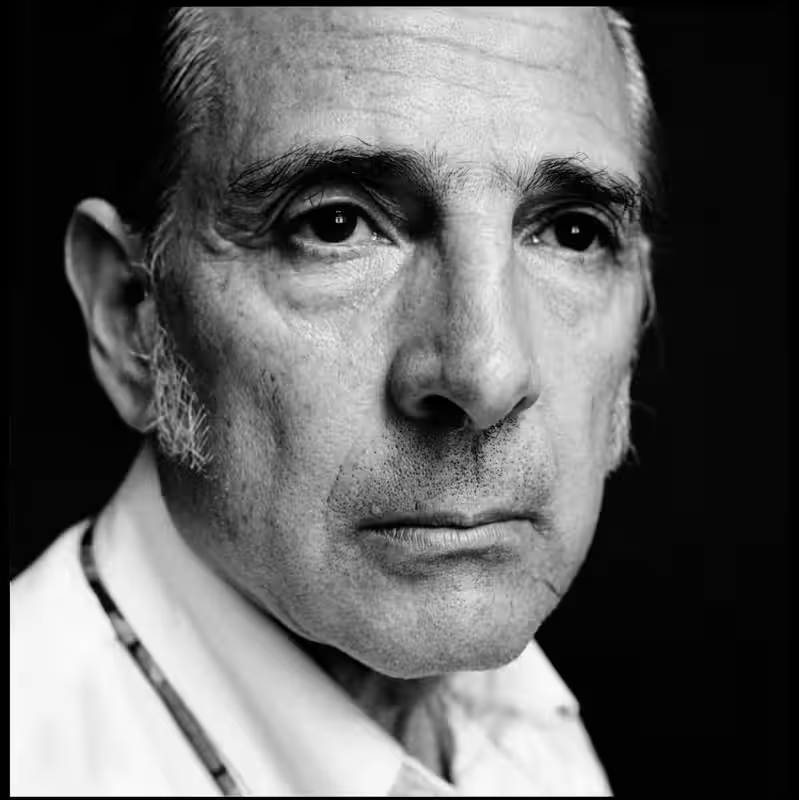

John Searle, the provocative and influential philosopher whose sharp critiques of artificial intelligence reshaped debates about consciousness, language, and what it means to be human, has died at age 93. His legacy is as complex as his ideas—celebrated for intellectual brilliance, yet shadowed by sexual harassment allegations that abruptly ended his academic career.

John Searle’s Intellectual Legacy

For decades, John Searle stood at the forefront of philosophy of mind and language. A longtime professor at the University of California, Berkeley, he was best known for his 1980 thought experiment, the “Chinese Room,” which argued that even the most sophisticated computer program—no matter how convincingly it mimics understanding—does not truly “think” or possess consciousness.

“Syntax is not sufficient for semantics,” Searle famously declared, challenging the core assumptions of strong AI. His argument became a cornerstone in philosophy, cognitive science, and AI ethics, sparking decades of rebuttals, defenses, and classroom debates.

A Career Marked by Boldness—and Controversy

Searle was renowned for his combative style and unapologetic clarity. He clashed with titans like Daniel Dennett and Hubert Dreyfus, and never shied from public intellectual sparring. But in 2017, his career came to a sudden halt when multiple women accused him of sexual harassment.

An internal UC Berkeley investigation found credible evidence that Searle had engaged in unwelcome conduct toward students and junior colleagues. Though he denied the allegations, the university stripped him of emeritus status and removed his name from campus honors. He retired in disgrace, his public presence fading almost overnight.

Key Contributions of John Searle

| Concept | Year | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese Room Argument | 1980 | Challenged the notion that machines can possess true understanding |

| Speech Act Theory | 1969 | Expanded on J.L. Austin’s work; explained how language performs actions |

| Biological Naturalism | 1990s | Argued consciousness arises from biological processes, not computation |

| Critique of Strong AI | Ongoing | Influenced AI ethics, robotics, and philosophy curricula worldwide |

Reactions from the Academic World

Tributes poured in with nuance. “Searle forced us to ask the hard questions about mind and machine,” said Dr. Susan Schneider, a philosopher of AI at Florida Atlantic University. “Even when we disagreed, we couldn’t ignore him.”

Others were more measured. “His ideas were foundational, but we must also remember the harm he caused,” tweeted Dr. Kate Manne, a feminist philosopher at Cornell. “Legacy is not just about intellect—it’s about integrity.”

Why Searle Still Matters in the Age of AI

As generative AI systems like ChatGPT and Claude blur the lines between simulation and sentience, Searle’s warnings feel eerily prescient. He never denied AI’s utility—he simply insisted it wasn’t “alive” in any meaningful sense.

“People confuse performance with understanding,” he told The New York Times in 2014. “A thermostat doesn’t ‘want’ to keep the room warm. And a chatbot doesn’t ‘know’ what it’s saying.”

In an era racing toward artificial general intelligence, his voice—flawed but fiercely rational—remains a necessary counterweight.

Personal Life and Final Years

Born in Denver in 1932, Searle studied at the University of Wisconsin and later Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar. He joined Berkeley’s faculty in 1959 and remained there for over 60 years. He is survived by his wife, Dagmar Searle, and two children.

Though largely out of the public eye after 2017, former students say he continued writing privately, grappling with the same big questions until the end.